A proud history at the forefront of Australian journalism

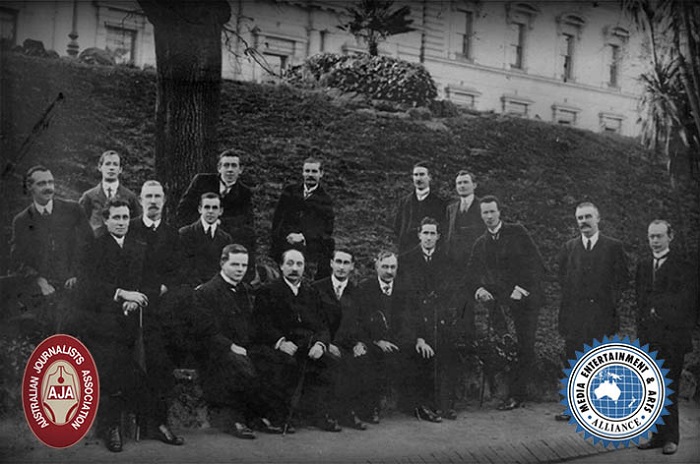

The federal council of the Australian Journalists Association gathers in Melbourne for its inaugural conference, March 1911.

The federal council of the Australian Journalists Association gathers in Melbourne for its inaugural conference, March 1911.

The MEAA Media section has a century of experience campaigning on behalf of the profession, making it one of the oldest media unions in the world.

MEAA Media is the name for the media workers section of MEAA. The section traces its history from 1910 with the foundation of the Australian Journalists’ Association which was formed at a meeting of journalists in Melbourne after several unsuccessful attempts to form a bond or union as a professional association for journalists.

At the time, journalists were often working piece rates of “a-penny-a-line”. As a reporter on a daily newspaper, you were probably paid in the region of £3 or £4 per week for working something in excess of 60 hours – across at least six days a week. That is, of course, if you were paid a weekly wage at all. One of those journalists working as a "penny-a-liner" was Keith (later Sir Keith) Murdoch, father of Rupert, who was scratching a living from piece work as a federal parliamentary reporter for The Age in Melbourne (the then national capital).

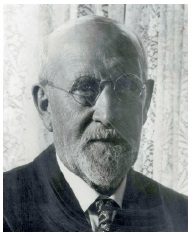

The 1910 meeting was called by Melbourne Herald reporter B.S.B. “Bertie” Cook. He had begun work at the paper as a copy boy, aged 12. After 10 years he was a reporter earning £3 for a 70-hour week. Concerned by journalists' working conditions, he joined with colleagues in several failed attempts to form an effective industrial association. But in 1910 Cook saw a new opportunity under the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 for journalists to register as an industrial organisation. The Act provided that “an employer shall not dismiss an employee or injure him in his employment or alter his position to his prejudice by reason of the circumstance that the employee is entitled to the benefit of an industrial agreement or award”.

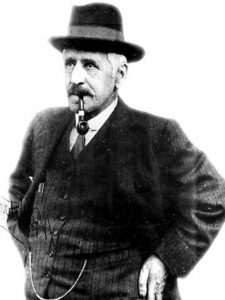

Bertie Cook - became member #1 of the new Australian Journalists' Association

Having taken advice from Prime Minister Alfred Deakin and the federal industrial registrar A.M. Stewart, Cook was told that the legitimacy of registration by journalists as an industrial organisation was unclear and there would have to be a test case to determine this.

On December 1 1910, Cook sent the following letter out to journalists around the country:

A meeting of journalists, i.e. persons professionally and habitually engaged on staff of newspapers or periodicals, will be held at the cafe in the basement of the Empire buildings, Flinders St., Melbourne on Saturday Dec 10th at 8pm sharp for the purpose of considering the question of forming an organisation to secure registration under the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act.

You are invited to be present and to extend an invitation to any other qualified person with whom you are acquainted.

On behalf of the committee,

Yours faithfully

B.S.B. Cook

Melbourne Herald

On December 10, more than 100 journalists crowded into the cafe (262-268 Flinders Street, Melbourne). Cook says this was “a fair proportion of journalists, in those days, who would be qualified to attend. Some of these were not too sure about what they were getting themselves into, feeling it would be “infra dig for the ‘gentlemen of the Press’ to have to seek the protection of the law in arranging their working hours and salaries”, but “after this is seemed as if the floodgates of discontent had broken their banks and speaker after speaker told of the intolerable hours they had to work and of the miserable salaries they were getting”. Sound familiar?

The Empire Building in Flinders Street, Melbourne - the cafe in the basement was the site of the first AJA meeting.

A secret ballot was held on the motion:

That this meeting of press writers of Australia affirms the desirability of forming an organisation for registration under the Conciliation and Arbitration Act of Australia.

While some abstained, the motion was passed 78 to nine.

James McLeod of The Age was elected president; A.N. “Arthur Norman” Smith, a journalist who ran his own press agency, became senior vice-president; and Bill A. Brennan and William Letcher – both from The Argus – were elected junior vice-president and treasurer respectively. Cook was appointed secretary. Smith took over the presidency soon afterwards.

Smith, whose bequest was to found the annual A.N. Smith Lecture to the University of Melbourne, “recognised that any improvement in wages and conditions would ultimately increase his own expenses”, became a key player in the establishment of the AJA.

The AJA lodged its application for registration on December 23 1910. It was met with an avalanche of objections from proprietors, who had enjoyed a status quo in which they could pay what they liked and demand their employees work crazy hours.

The application came before the registrar on April 11 1911, with Frank Brennan, KC (Bill Brennan’s brother) for the AJA, against a Bar team of three, including two future Supreme Court judges, for the proprietors.

The arguments took several days, but Brennan’s case was strong, stating successfully that there was no objection under the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 to journalists registering as a profession. The employers, it was later revealed, had not been united in all of their objections. On May 24 1911, the registration was granted and the AJA became the first association of journalists in Australia.

A national association was quickly developed. On January 17 1911, Melbourne became the first district branch of the AJA to be approved. Brisbane followed on February 14, followed by Adelaide (March 24), and NSW (April 23). On July 19, Hobart was admitted to AJA membership, followed by Perth on September 29.

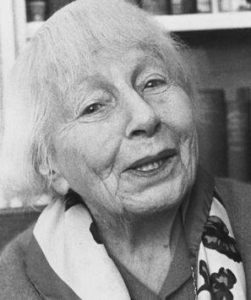

Among the notable foundation members of the AJA were Stella Allen of The Argus and Maisie "May" Maxwell of the Melbourne Herald. In 1904 Allen had begun a weekly section in The Argus called "Women to Women" writing under the nom de plume "Vestra" – believed to be the first section dedicated to women's affairs, children's interests and community welfare. She became a delegate for Australia to the fifth assembly of the League of Nations at Geneva and was a delegate to the second Pan Pacific Women's Conference in Hawaii in 1930.

Maxwell, who had begun a career on the stage, had begun writing for Perth's Sunday Times; quickly concluding that journalism offered a more stable career than the theatre. In 1910 she was invited to edit the Melbourne Herald's weekly page for women. In 1921, the new editor Keith Murdoch asked her to make it a daily feature. Maxwell served on the AJA's Victorian committee and became an honorary life member in 1960. In 1969 she was awarded an OBE for services to journalism.

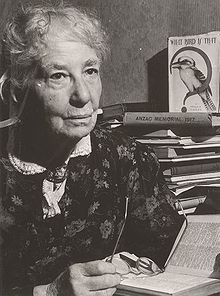

LtoR: founder members of the AJA - Stella Allen (courtesy Melbourne Press Club) Maisie "May" Maxwell

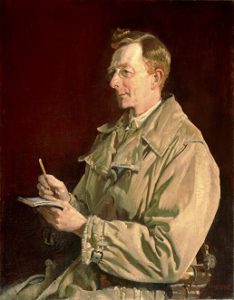

Anther foundation member was C.E.W. (Charles) Bean. Bean was a contributor to the Sydney Morning Herald. The Australian government of Prime Minister Andrew Fisher had promised the AJA that the association would be given full responsibility to select the country's first official war correspondent to cover the AIF's participation in the Great War. As Clem Lloyd writes in the AJA history Profession Journalist: "The AJA's central committee called for nominations, rejecting some because they were unfinancial. It conducted a ballot in which the top candidates were C.E.W. Bean with nine votes, Keith Murdoch with eight, and Oliver Hogue with six. A further preferential ballot was held with Bean beating Murdoch seven to three. Murdoch was nominated as the substitute if, for whatever reason, Bean was unable to go. (It is interesting to speculate what might have been ... if the ballot had gone the other way). Bean was given the honorary rank of Captain and paid a salary of £600 a year."

Both Bean and Murdoch would play different but crucial roles at Gallipoli, with Bean going on to write the official war history. Murdoch, who was also a foundation member of the AJA, welcomed the union ending the era of "penny-a-line" piece work, saying: “The AJA ... got me a rise of one pound a week and relief from slavish conditions." He later wrote:

“The AJA has not only greatly improved conditions for the journalists, but has also done a great deal for Australian newspapers.”

LtoR: candidates in the AJA ballot to become Australia's first war correspondent - Charles Bean (courtesy Australian War Memorial) and Keith (later Sir Keith) Murdoch

The next major battle for the fledgling AJA was the establishment of an industrial award to cover the various duties of journalists. A committee was formed for this purpose and in November 1911 the “Blue Log” of Claims (for the tinted legal foolscap it was typed on) of journalists’ duties was lodged with newspaper proprietors.

A.N. Smith described the Blue Log as the AJA’s Magna Carta and Bill of Rights rolled into one. “It contained the basic laws of a grading system, the proportion of grades, the limiting of hours of working and provided for holiday requirements. Finally, it submitted a scale of pay.” Under the proposed staff-grading system a senior reporter on a “Class A” morning newspaper would earn a minimum of £7 a week; a first-year cadet £1 and 10 shillings. Senior reporters had to make up at least three-fifths of a newspaper’s staff. Working hours were fixed at 48 hours per week, with one clear day off in seven.

In a rare move for that era, the Blue Log made no distinction between the rates of pay for men and women – establishing the principle that was almost 60 years ahead of the Commonwealth Arbitration Commission’s equal pay decision in 1969.

A conference was held on December 14, 1911, between representatives of the employers and the AJA, at which there was stalemate between the employers’ position and the AJA’s log of claims and a brief walkout by AJA representatives.

A compromise was eventually reached and the agreement filed in the Arbitration Court, for 12 months dating from January 1 1912. The breakthrough was hailed by Britain’s National Union of Journalists as “an agreement which revolutionised the condition of daily newspaper staffs”.

The battle to improve the lot of journalists in Australia had begun. In 1912 there was a strike at the Perth Daily News over pay rates – the first by Australian journalists (and possibly by journalists anywhere in the world). Staff at The Mercury in Hobart failed to win parity with Melbourne and Sydney rates, but the AJA negotiated some salary increases, three weeks’ paid holiday a year and a limit of 48 hours a week. By 1913 the AJA had 765 members, 530 of them in Victoria and NSW.

Guiding the fledgling union on this path for the next 30 years was Sydney Ernest Pratt. A member of a prominent family of journalists, Syd Pratt had worked on the Sydney Morning Herald and the Mining Standard in Melbourne. While honorary secretary of the AJA's South Australian district in 1911-19, Pratt was a member of the team that prepared the union's submission in proceedings before (Sir) Isaac Isaacs in the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration that led to the first Federal award covering journalists.

In 1919 he became general secretary of the AJA. The Australian Dictionary of Biography says Pratt was an adroit conciliator, settling most disputes and concluding industrial agreements with newspaper proprietors by extensive negotiations. In 1927-28 Pratt and the AJA's president Syd Deamer successfully argued before Robert (later Sir Robert) Menzies, who had been appointed arbitrator, that all newspaper literary staff should be graded as journalists covered by industrial awards. The journalists' grading system continues to this day. During the 1930s Pratt also worked assiduously to prevent substantial cuts in newsroom jobs and to minimize wage reductions at a time of large-scale labour attrition. He adeptly guided the AJA through the Great Depression, but later conceded that the pressures on the association in those years had "nearly wrecked it". In 1954-55 he directed a protracted and arduous industrial-award hearing which resulted in significant improvements in salary and conditions; it was one of the few occasions when he was forced into a court battle with proprietors.

Pratt's early work for the union quickly had the AJA right in the midst of industrial fray. The AJA's first industrial award was signed in May 1917 and established a 46-hour week with one-and-a-half days off, provision for overtime, three weeks’ paid holiday, paid sick leave, and the principle of equal pay for men and women in the profession.

Ratifying the 1917 agreement, Justice Isaacs commented that “No just comparison can be made by journalism with any other occupation. Journalism is a profession, sui generis ['unique, in a class by itself']. I cannot measure it by what is paid for totally different work.”

A leading article the AJA house publication The Journalist commented that the result of the case “will be to raise the prestige and status of the profession. Journalism will become less a means of earning a living and more a profession imbued with high ideals”.

So effective was this early work by the AJA, that the union – and its agreement – became a blueprint for similar organisations developing around the world. Britain’s NUJ, which had been founded only two years before the AJA, looked on in envy at the agreement as “an example for emulation” by its journalists.

Also in 1917, John Curtin, future Second World War Prime Minister, applied for membership of the AJA (he soon became WA district president) and the original Melbourne Press Club is formed.

The Australian Journalists' Association annual council, A.N. Smith (front centre) – Sydney, February 1912.

In 1919 Bulletin founder J.F. Archibald died, leaving a large share of his estate for the AJA’s NSW District to establish a benevolent fund “for the relief of distressed Australian journalists”. The fund continues this work today – as do other AJA/MEAA-associated benevolent funds in across the country. A year later, newspaper artists and photographers come under the AJA’s umbrella. In its 1926 report on the working conditions of journalists in 33 countries, the International Labour Office at Geneva wrote:

“Australian journalists are among the members of the profession possessing the most satisfactory status … No other country has such minute regulations on the subject of hours of work.”

In 1928 Robert Menzies chaired a tribunal to overhaul the Metropolitan Dailies’ Agreement. Changes include improved conditions for journalists, replacement of the old grading system with four news grades of A, B, C and D, and the introduction of a four-year cadet system with proper recruitment and training.

By 1930 the AJA has 1900 members – about 90 per cent of those eligible to join.

The ideals of the AJA as a professional association for Australia’s journalists were to achieve their fullest expression in 1944 with the AJA Code of Ethics for journalists, in the face of opposition from proprietors – many of whom refused to display the eight-point code in their newsrooms. To promulgate and enforce the code, each state set up an Ethics of Judiciary Committee, which administered the code and dealt with complaints. The code was revised substantially in 1984, when it was issued as a set of 10 clauses, and again in 1999 when it became the 12-clause MEAA Journalist Code of Ethics that operates today.

One of the most significant contributions of the AJA to journalism as a profession has been the establishment of the Australian Press Council in 1976 after more than 20 years of lobbying by the union. The Council comprises representatives of the proprietors, the union and the public.

The union’s core focus on arbitration and conciliation has been challenged on a number of occasions: in 1944 and 1955 in support of colleagues in the print unions— disputes that ended when AJA strike newspapers (in 1944, the News and in 1955, the Clarion) were created and sold up to 200,000 copies.

Industrial action has rarely been over money, with the union successful in its wage negotiations. Instead, strikes and other action have been over proprietorial interference in content, to secure adequate compensation for the introduction of new technology or over the devaluing of journalistic skills.

The AJA was central to the establishment of journalism as a profession. In 1956, the chairman of Ampol, Sir William Gaston Walkley, set up a foundation to run awards for journalistic excellence. Since its inception, the Walkley Awards have grown from five to more than 30 categories and introduced a raft of professional development initiatives.

On May 18 1992 MEAA was formed through the merging of the AJA, Actors’ Equity and the Australian Theatrical and Amusement Employees’ Association. Since amalgamation, the Symphony Orchestra Musicians’ Association and the NSW Artworkers’ Union have joined MEAA and the Screen Technicians’ Association of Australia has come under the MEAA banner.

In 2000 the Walkley Foundation was constituted under MEAA by-laws as an autonomous organisation; today it operates as a company limited by guarantee. Its tasks are to organise the Walkley Awards, advance the interests of professional and ethical journalism, implement education and training programs for journalists, and to advance the interests of the MEAA Media section. The Walkley Foundation Limited directors are the three nationally elected officials of the MEAA Media section, the MEAA CEO and the Walkley Board chair. Together, they may appoint up to two additional directors.

MEAA also led the way in campaigning for equal pay and status for women journalists, and was the first union to introduce a quota system to ensure equal representation of women on its governing body. MEAA has established Women in Media as a mentoring and networking initiative for members. Women in Media campaigns for gender equity and has released a study of the gender pay gap in the profession: Mates Over Merit - The Women in Media Report – A study of gender differences in Australian media.

MEAA has recognised Australia’s shifting geopolitical priorities and has moved towards greater involvement in regional issues, hosting the Asia-Pacific office of the International Federation of Journalists at MEAA’s federal headquarters in Sydney.

Mindful of the changing nature of the media industry, MEAA has also established a special category of membership, Freelance Pro, which provides members with professional indemnity and public liability insurance as well as training in the MEAA Journalist Code of Ethics and the latest developments in media law. Freelance Pro members are identified with a special membership card and the use of a trust mark for marketing their business.

MEAA has also been at the forefront in campaigning for press freedom, releasing an annual report cataloguing the state of press freedom in Australia each May (around UNESCO World Press Freedom Day May 3). MEAA regularly lobbies on press freedom matters and is a member of the Australia’s Right To Know media industry group.

In 2005, MEAA established the Media Safety and Solidarity Fund (MSSF) which is supported by donations from Australian journalists and media personnel, to assist colleagues in the Asia-Pacific region through times of emergency, war and hardship.

MEAA’s Media section welcomes as members people who work in Australia’s media and communications industry including those working on any platform (print, broadcast, digital); as reporters, editors, photographers, designers, producers, artists, cartoonists, sub-editors – including those working as full-time, part-time and casual employees or as freelance independent contractors, and in public affairs and communications. Today, MEAA’s Media section has about 5500 members.

LtoR: AJA members Banjo Paterson and Dame Mary Gilmore

The men and women of the fledgling Australian Journalists’ Association helped turn an underpaid and often ramshackle craft into a profession. Among the many notable members of the AJA/MEAA are: Caroline Jones, Kenneth Slessor, A.B. "Banjo" Paterson, Laurie Oakes, Warren Denning, Dame Mary Gilmore, Otto Beeby, Liz Jackson, Bruce Petty, C.E.W. Bean, Les Carlyon, Wendy Bacon, Stella Allen, Mark Colvin, Kerry O'Brien, Syd Deamer, Rupert Lockwood, Russell McPhedran, Ron Tandberg, George Godfrey, Barrie Cassidy, Helen Garner, John Spooner, Syd Pratt, Michael Gordon, Maisie Maxwell, Chris Masters, Roy Masters, Deb Masters, John Curtin, Heather Ewart, Bob Bottom, Paul Lyneham, George Brickhill, Peter Bowers, Michael Gordon, Paul Brickhill, Billy Hughes, Marien Dreyer, Keith Murdoch, Anne Summers, Phil Chubb, Barrie Dunstan, Michelle Grattan, Graham Perkin, Les Tanner, and Andrew Olle.